Acknowledgement

This guidance uses the terms ‘woman’ and ‘mother,’ which are intended to be inclusive of anyone who may use other self-identifying terms and aims to encompass all for whom this guidance is relevant.

Consumer Engagement Statement

All interactions between health care staff with consumers (women, mothers, patients, carers and families) should be undertaken with respect, dignity, empathy, honesty and compassion.

Health care staff should actively seek and support consumer participation and collaboration to empower them as equal partners in their care.

Definitions/abbreviations

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| CPOs (Carbapenemase Producing Organisms) | Bacteria that have developed resistance to several antibiotics, including carbapenems |

| CSU | Catheter specimen of urine |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| ESBL (extended spectrum beta lactamase) | An enzyme found in some strains of bacteria. ESBL-producing bacteria can't be killed by many antibiotics such as penicillins and some cephalosporins. |

| FiO2 | Fraction of inspired oxygen |

| Group A streptococcus (GAS) infection | Also known as Streptococcus pyogenes |

| HVS | High vaginal swab |

| LVS | Low vaginal swab |

| MAP | Mean arterial blood pressure Diastolic BP + 1/3 (systolic BP – diastolic BP) |

| MROs (multi-resistant organisms) | Organisms that are resistant to some antimicrobials |

| MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) | Staphylococcus aureus that is resistant to methicillin/ flucloxacillin |

| MSU | Midstream urine |

| PaO2 | Partial pressure of oxygen (assessed with arterial blood gas) |

| Puerperal sepsis | Peripartum sepsis resulting from the genitourinary tract |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| Sepsis | A life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. A diagnosis of sepsis is considered in any patient with an acute illness or clinical deterioration that may be due to infection6 Sepsis is a life-threatening condition |

| Septic shock | Septic shock is defined as ‘a subset of sepsis in which the underlying circulatory, cellular and metabolic abnormalities are associated with a greater risk of mortality than sepsis alone6 |

Local health service adaptation

- The specific areas that may need local adaptation are:

- Pathways of escalation, including the availability of senior staff, of expertise in infectious diseases and when intra- or inter-hospital transfer is required.

- Choice of antibiotics depending on local conditions – this is particularly relevant for aminoglycosides. Regimens have been provided for gentamicin, tobramycin and amikacin.

Background

Sepsis can be a life-threatening condition that requires a time critical response. The effects can be life-changing, leading to lasting maternal illness affecting the woman’s passage to motherhood, the establishment of breastfeeding and her ongoing connection to her baby.

Clinicians should provide open and consistent communication with the woman (when feasible) and her support people.

Common causes of sepsis in this cohort are:

- Septic abortion, chorioamnionitis, pneumonia/influenza, pyelonephritis, wound infection, mastitis, endometritis. (with or without retained products of conception)

- E. coli is the most common cause of maternal bacterial infection. The most frequent cause of maternal death from sepsis is infection with Group A streptococcus (GAS) species. Invasive GAS infection typically manifests as sepsis, endomyometritis, cellulitis, necrotising fasciitis, or toxic shock syndrome.

Recognising sepsis

Recognition of sepsis is a critical first step in appropriate assessment and management, regardless of the care setting, in community or a hospital. Consider sepsis in all patients with acute illness or physiological deterioration who may have an infection and ask the question ‘could it be sepsis?’ as part of regular clinical assessments.

In pregnancy, diagnosis may be more difficult because physiological changes associated with pregnancy and/or labour may mimic the signs of sepsis (e.g. elevated heart rate and respiratory rate, lower blood pressure, raised white blood cell count, increased lactate during labour).

Risk factors that may assist with the early recognition of maternal sepsis could include bleeding in pregnancy, miscarriage, prolonged rupture of membranes, prolonged labour, retained products of conception and fetal tachycardia.

This guidance utilises a modification of the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) 2020 screening criteria.2 The CMQCC reports fewer missed cases with fewer false positives, compared with other screening tools.

Initial sepsis screen

Recognise

Consider sepsis if the woman has any of the following:

| Site of concern |

|

|---|---|

| Fevers and rigors |

|

Neurological

|

|

Poor peripheral perfusion

|

|

| Chest |

|

| Abdomen |

|

| Malodorous vaginal discharge |

|

| Urine |

|

| Skin and soft tissue |

|

| Line insertion sites |

|

| AND two or more of the following | |

| Blood pressure |

|

| Other observations |

|

If the initial sepsis screen is positive and there is clinical suspicion or evidence of infection, start treatment.

Respond

Rapid response - most tasks will need to be carried out concurrently.

| Oxygen |

|

|---|---|

| IV access |

|

| Investigations |

|

| Observations |

|

| Antibiotics |

|

Source screening

Do not delay antibiotic treatment for culture collection. |

|

| Fluid management |

|

| Fetal considerations |

|

| Escalate |

|

Confirmation of sepsis

Further tests: These tests/observations may be useful for considering care setting including transfer to a higher level of care or downgrading care. They will not be required for all women and should be undertaken in consultation with senior clinicians.

| Measure | Criteria (any one is diagnostic) |

|---|---|

Respiration PaO/FiO2 |

|

| Coagulation (FBE, INR, APTT) |

|

| Liver (LFT) |

|

Cardiovascular

| Persistent hypotension (SBP < 85 mmHg) after fluid administration or MAP < 65 mmHg Or BP > 40 mmHg decrease in SBP |

Renal (U&E, urine output)

|

|

| Mental status assessment |

|

| Lactate |

|

Ongoing management

| Reassess management |

|

|---|---|

| General measures |

|

Antibiotic prescribing and administration

1. Prescribe antibiotics

- Unknown source or chorioamnionitis These regimens are for initial intravenous doses for sepsis/septic shock and should be used for all women to minimise delays to administration (Table 1).

- Known source: According to Therapeutic Guidelines3 or local, evidence-based guidelines.

- Also consider additional risk factors (Table 2).

2. Administer complete dose of antibiotics within 60 minutes of consideration of sepsis

- In the setting of a critically unwell woman, antibiotics can safely be given at faster rates than in usual practice and multiple antibiotics can be given concurrently, intravenously at different sites4 (Table 3). Hospital protocols will dictate administration method of choice – e.g. syringe pump, slow push.

3. Seek pharmacist/infectious diseases advice for ongoing maintenance dosing, including in the setting of renal impairment or obesity.

4. Aminoglycosides:

- Each hospital should choose a single agent from gentamicin, amikacin or tobramycin, in consultation with local expertise and then use that agent consistently (Table 1).

Additional considerations

- Abnormal temperature and elevated heart rate may be the most common combination, however not all women with sepsis will have a fever at ≥ 38.0°C.

- Maternal corticosteroid administration often increases the white blood cell count, but the suspicion for infection should not be discounted without further evaluation. White blood cell values peak 24 hours after administration and return close to baseline values by 96 hours after administration.

- Support for ongoing breastfeeding or assistance with expressing of breast milk, in keeping with the woman’s wishes, should be offered.

- Women and their families should be informed that they have/had a diagnosis of sepsis and provided with appropriate opportunities for information provision and debriefing.

Summary flow chart

Think sepsis if any 2 of the following are present, plus a clinical suspicion of sepsis:

- Temperature < 36oC or ≥ 38oC

- Heart rate > 110 for at least 15 minutes

- Respiratory rate > 24 per minute for at least 15 minutes

- White cell count > 15 × 109 or < 4 × 109

- MAP < 65 mmHg.

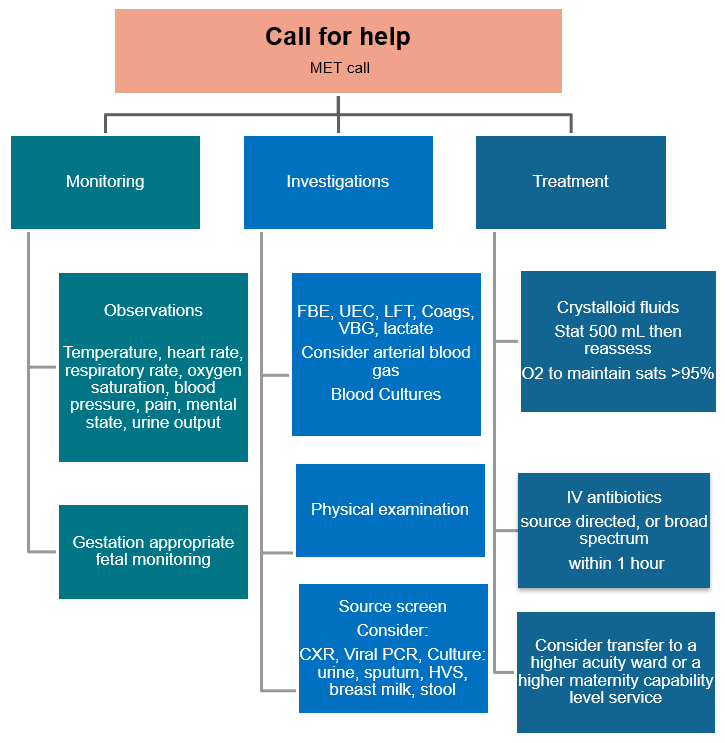

Call for help flowchart

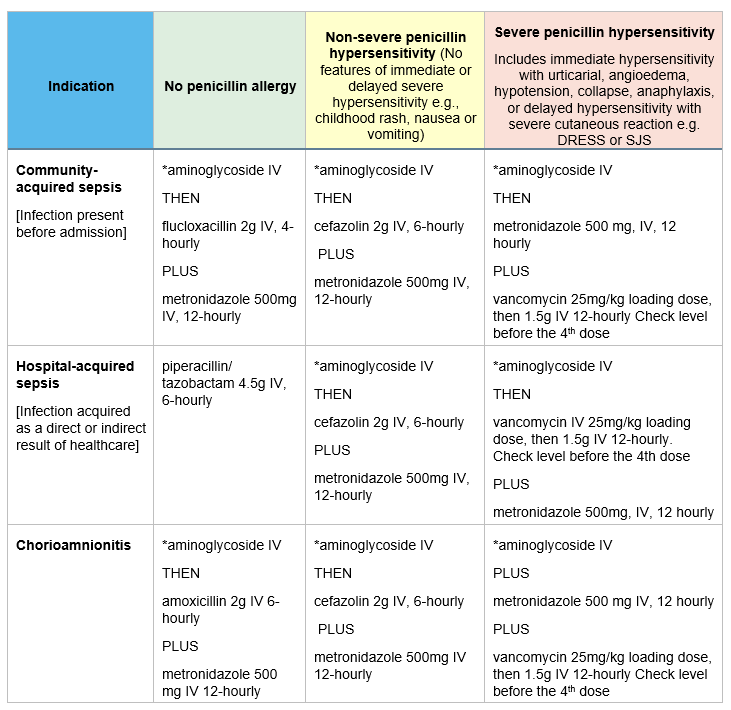

Table 1: Antibiotic recommendations: Unknown source of infection or chorioamnionitis

For women with allergies to any of the antibiotics above, escalate for specialist advice.

*Aminoglycoside:

Each hospital should choose their primary aminoglycoside in accordance with local susceptibility patterns and in conjunction with regional partners and local expertise. Dosing is based on estimated or measured weight, rather than ideal body weight. (adjusted body weight for women with a BMI>30)

Use the same dose regardless of renal function for initial dose.

Gentamicin – initial dose 7 mg/kg for septic shock to maximum 600 mg (Routinely used in pregnancy)

Amikacin – 28 mg/kg to maximum 2,800 mg

Tobramycin 7 mg/kg to maximum 600 mg

Table 2: Additional antibiotic considerations, including Group A Streptococcus

| Indications | Antibiotic |

|---|---|

Septic shock: persisting hypotension despite resuscitation

| ADD vancomycin 25mg/kg loading dose, then 1.5g IV 12-hourly (if at risk of MRSA colonisation and/or presence of lines) |

Group A Streptococcus Contact with GAS infection case Toxic shock | ADD clindamycin 600mg IV 8 hourly CONSIDER IV immunoglobulin 1-2 g/kg IV (with ID consultation) |

| Suspected Neisseria meningitidis infection, or suspected CNS infection | ADD ceftriaxone 2g, IV, 12 hourly |

Woman with prior history of multi-resistant Gram-negative colonisation – e.g. CPOs, ESBLs, multi-resistant organisms (MRO), or Overseas hospitalisation or travel in the previous 6 months | REPLACE all empiric antibiotics with single agent meropenem 2g, IV, 8 hourly |

| MRSA carrier: Based on previous swabs/ cultures or residence in NT, remote communities in FNQ or northern WA or recent incarceration, or recent prolonged hospital stay | ADD vancomycin 25mg/kg loading dose, then 1.5g IV, 12-hourly |

Table 3: Rapid antibiotic administration advice

| Antibiotic | Administration instructions |

|---|---|

| Amoxycillin | 1g with 20 mL water for injection over 3–4 minutes (2x1g amoxicillin vials are needed) |

| Clindamycin | Dilute 600 mg in 50 mL sodium chloride 0.9% and infuse over 20 minutes |

| Ceftriaxone | 2g with 40 mL water for injection and infuse over 5 minutes |

| Cefazolin | 2g with 19 mL water for injection and infuse over 5 minutes |

| Flucloxacillin | 2g with 40 mL water for injection and infuse over 6–8 minutes |

| Gentamicin | Dilute with 20 mL sodium chloride 0.9% and infuse over 3–5 minutes |

| Metronidazole | Infuse over 20 minutes |

| Piperacillin/ tazobactam | 4.5g with 20 mL water for injection and infuse over 5 minutes |

Vancomycin

| 500 mg with 10 mL water for injection and 1g with 20 mL water for injection to make a concentration of 50mg/mL. Dilute to 5 mg/mL with sodium chloride 0.9%, i.e. dilute 1g to at least 200 mL.* 1g may be infused over 1 hour, 1.5g over 1.5 hours and 2g over 2 hours. * If fluid restriction, max concentration 10 mg/mL, i.e. dilute 1g in 100 mL |

Table 4: White cell count in pregnancy – normal range: a reference table for clinicians

| Non pregnant adult5. | 3.5–9.1 × 103 mm3 |

| First trimester | 5.7–13.6 × 103 mm3 |

| Second trimester | 5.6–14.8 × 103 mm3 |

| Third trimester | 5.9–16.9 × 103 mm3 |

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Maternal deaths in Australia. Cat. no. PER 99. 2020 [cited 2024 May 01]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/maternal-deaths-australia

- Gibbs R, Bauer M, et al. Improving Diagnosis and Treatment of Maternal Sepsis: A Quality Improvement Toolkit. [Internet]. Stanford CA., California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative; 2020 [cited 2024 May 7]. Available from: https://www.cmqcc.org/resources-toolkits/toolkits/improving-diagnosis-and-treatment-maternal-sepsis

- Therapeutic Guidelines: Antibiotic. Available from: https://tgldcdp.tg.org.au/guideLine?guidelinePage=Antibiotic&frompage=etgcomplete

- Australian Injectable Drugs Handbook (AIDH) 9th Edition. Available from: https://www.shpa.org.au/publications-resources/aidh

- Abbassi-Ghanavati M, Greer LG, Cunningham FG. Pregnancy and Laboratory Studies: A Reference Table for Clinicians. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2009 Dec;114(6):1326-1331. DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c2bde8.

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Sepsis Clinical Care Standard. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2022. Available from: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/sepsis-clinical-care-standard-2022

Additional resources

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Review of trigger tools to support the early identification of sepsis in healthcare settings. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2021. Available from: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/review-trigger-tools-support-early-identification-sepsis-healthcare-settings.

- Bowyer L, Cutts BA, Barrett HL, Bein K, Crozier TM, Gehlert J, Giles ML, Hocking J, Lowe S, Lust K, Makris A, et al. SOMANZ position statement for the investigation and management of sepsis in pregnancy 2023. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2024 Jun 24. doi: 10.1111/ajo.13848.

- Yahya FB, Yousufuddin M, Gaston HJ, Fagbongbe E, Rangel Latuche LJ. Validating the performance of 3 sepsis screening tools in patients with clinical chorioamnionitis. AJOG Glob Rep. 2023 Oct 3;3(4):100271. doi: 10.1016/j.xagr.2023.100271. PMID: 37885969; PMCID: PMC10598707.

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Lactate in the deteriorating patient and sepsis Factsheet

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Antimicrobial guidance for sepsis programs Factsheet

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Information for people with sepsis and their families (for adults) Factsheet.

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care.National Consensus Statement: Essential elements for recognising and responding to acute physiological deterioration

Citation

To cite this document use: Safer Care Victoria. Maternal Sepsis Guideline [Internet]. Victoria: Maternity eHandbook; 2024 [cited xxxx] Available from: https://www.safercare.vic.gov.au/clinical-guidance/maternity

Acknowledgement

Safer Care Victoria would like to acknowledge Victoria’s four tertiary maternity services, the Royal Women’s, Mercy Hospital for Women, Joan Kirner Women’s and Children’s and Monash Women’s, for their significant contribution in the development of this guidance, as part of the Maternity and Neonatal eHandbook updating project 2023.

Download

Get in touch

Version history

First published:

December 2024